The Prodigal – Lk 15 (1)

A respected man was blessed with two sons. One day, his younger son says to him, “Father, give me the share of the property coming to me.”

The father (should have) said, “WHAT ?!#?! I’m as good as dead to you? You wish me to die? Have you no sense of shame son? You have an obligation as the younger son to stay home and take care of me and your mother. Nobody insults my honor like that. You have ruined our family name. You want me dead…I pronounce you dead, and out of the family.” That is what all the village bystanders expected.

Instead, the father quietly gathers the title documents from the house. Not to disown his son by taking away his inheritance, but to give him 1/3 of everything (the older brother got a double portion since he’s financially responsible for the family). In so doing, the father willingly bore shame upon himself. He knew the whole village was gossiping about him. He endured public disgrace to maintain relationship with his son.

Then the younger son goes out and sells the fruit orchard his grandfather planted many years ago. No Jew in that village would have touched land so shamefully acquired, so the son sold Yahweh’s Promised Land to a Gentile –an unspeakable taboo, and everyone would have hated him for it. By selling that land, he would have no way to provide for his family in the future, and no place to build a home for his children. He cashed out and left town, not thinking about his family or the future. He ruined his family’s reputation.

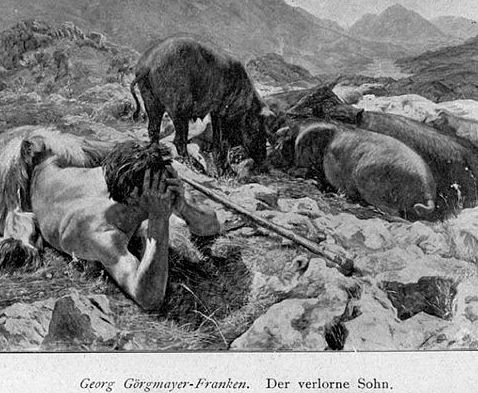

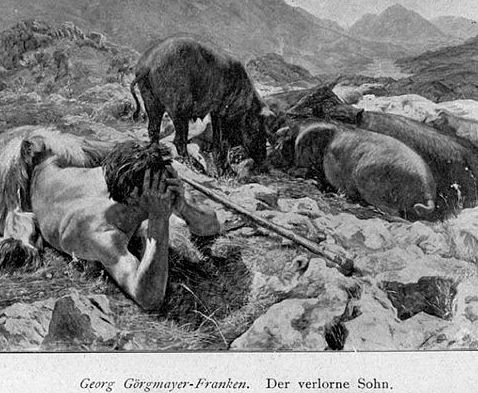

In the distant land he squandered all the money. Easy come, easy go. To make ends meet, the boy found himself eating with the pigs, actually begging to eat like the pigs. He lost all regard as a good Jew and all dignity as a human to just survive. He set out with hopes of freedom, but landed in slavery, scavenging in a pig pen.

He finally arrived back home, entirely dejected. His head was hanging low, sullied in shame. He was covered in pig filth. The defilement covered him from head to toe and his clothes were hardly recognizable. Even worse, he was empty-handed. Everybody in this part of the world knows you always return home with presents for the whole family. Returning empty-handed is humiliating, a sign of weakness.

The entire village eagerly awaited his return, not to welcome him, but to perform the ‘cut-off’ ceremony. One of the ancient traditions dictated that if a villager married an immoral woman or sold land to a Gentile, the village would smash a clay pot before him, then declare, “Away from us! You have nothing to do with us! You are cut-off.” The village waited to forever ratify his shame, publicly and completely. The crowds surrounded the younger son, screaming insults of scorn.

Just then, the father….

Click here to read the next posts.

This retelling on Luke 15 blends the research of Kenneth Bailey, my own Central Asian experiences, and some imagination to explain the honor-shame dynamics of ‘the gospel within the gospels.’

The father (should have) said, “WHAT ?!#?! I’m as good as dead to you? You wish me to die? Have you no sense of shame son? You have an obligation as the younger son to stay home and take care of me and your mother. Nobody insults my honor like that. You have ruined our family name. You want me dead…I pronounce you dead, and out of the family.” That is what all the village bystanders expected.

Instead, the father quietly gathers the title documents from the house. Not to disown his son by taking away his inheritance, but to give him 1/3 of everything (the older brother got a double portion since he’s financially responsible for the family). In so doing, the father willingly bore shame upon himself. He knew the whole village was gossiping about him. He endured public disgrace to maintain relationship with his son.

Then the younger son goes out and sells the fruit orchard his grandfather planted many years ago. No Jew in that village would have touched land so shamefully acquired, so the son sold Yahweh’s Promised Land to a Gentile –an unspeakable taboo, and everyone would have hated him for it. By selling that land, he would have no way to provide for his family in the future, and no place to build a home for his children. He cashed out and left town, not thinking about his family or the future. He ruined his family’s reputation.

In the distant land he squandered all the money. Easy come, easy go. To make ends meet, the boy found himself eating with the pigs, actually begging to eat like the pigs. He lost all regard as a good Jew and all dignity as a human to just survive. He set out with hopes of freedom, but landed in slavery, scavenging in a pig pen.

He finally arrived back home, entirely dejected. His head was hanging low, sullied in shame. He was covered in pig filth. The defilement covered him from head to toe and his clothes were hardly recognizable. Even worse, he was empty-handed. Everybody in this part of the world knows you always return home with presents for the whole family. Returning empty-handed is humiliating, a sign of weakness.

The entire village eagerly awaited his return, not to welcome him, but to perform the ‘cut-off’ ceremony. One of the ancient traditions dictated that if a villager married an immoral woman or sold land to a Gentile, the village would smash a clay pot before him, then declare, “Away from us! You have nothing to do with us! You are cut-off.” The village waited to forever ratify his shame, publicly and completely. The crowds surrounded the younger son, screaming insults of scorn.

Just then, the father….

Click here to read the next posts.

This retelling on Luke 15 blends the research of Kenneth Bailey, my own Central Asian experiences, and some imagination to explain the honor-shame dynamics of ‘the gospel within the gospels.’

I really appreciate your writing here, Jason. Nicely done, insightful. Thanks so much for this.

Thanks. The story gets better, you know! 🙂

I truly love this concept of Honor and Shame. It is really new concept for me which has blessed me deeply. Praise God for this. Blessed the man who brought this concept to bless God’s people around the world.