Guilt-Shame-Fear & Other Cultural Models

There are many models that explain how global cultures differ. They all simplify reality in different ways. This post shows how the guilt-shame-fear paradigm compares to other well-known cultural models.

1. Hofstede’s 6 Dimensions

An organizational anthropologist named Geert Hoftstede began working at Europe IBM in 1965. He founded the Personal Research department for IBM in Europe, which provided a global platform for cultural research. From 1967-73, he conducted a survey of national values among 117,000 IBM employees. Hofstede’s subsequent analysis identified six dimensions where national cultures differ.

- high-power distance vs. low-power distance

- collectivism vs. individualism

- weak certainty avoidance vs. strong certainty avoidance

- masculinity (task focus) vs. femininity (relational focus)

- long-term orientation vs. short-term orientation

- indulgence vs. restraint

Although these binaries were not unique to Hofstede, his scientific research helped legitimate the categories by providing a quantifiable theory for cultural differences. His international bestseller Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind (1991) mainstreamed the cultural model in academic and business circles.

2. Lingenfelter’s 6 Values

A similar model by Christian anthropologist Sherwood Lingenfelter is popular among Christian missionaries. In Ministering Cross-Culturally: An Incarnational Model for Personal Relationships (1986), Lingenfelter unfolds a model of basic values to help Christians understand the cross-cultural roots of relational conflict. Using illustrations from the Bible and his personal experience on the island of Yap, Lingenfelter explains six pairs of contrasting cultural orientations.

- time vs. event

- task vs. person

- dichotomist thinking vs. holistic thinking

- status focus vs. achievement focus

- crisis vs. noncrisis

- concealment of vulnerability vs exposure of vulnerability

Both Hofstede and Lingenfelter organize cultures along a continuum with opposite poles. This either-or dichotomy is a helpful and popular method for cultural analysis (especially for Westerners characterized by dichotomist thinking!). Generally speaking, their categories align with “innocence-guilt cultures” and “honor-shame cultures.”

3. Lewis’ LMR Model

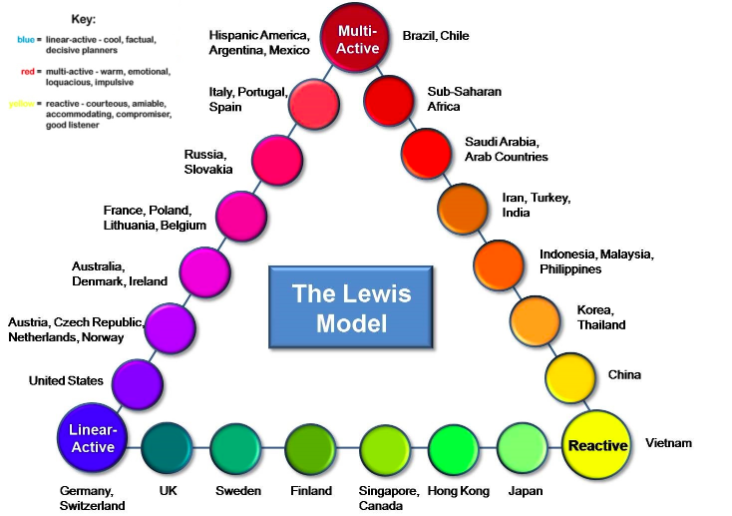

British polyglot Richard D. Lewis developed another cultural model called LMR to forecast cultural behavior. According to his book When Cultures Collide (1999), there are three main styles of cultural communication.

- Linear-active cultures are factual and decisive organizers, planners and schedulers (i.e., Germany).

- Multi-active cultures are lively multi-taskers who live according to the moment (i.e., Brazilians).

- Re-active cultures are courteous and calm listerners who respond carefully (i.e., Japanese).

Lewis places each culture type at the tip of a triangle, then locates countries by their communication style along the edge of the triangle, as seen below.

Similar to the guilt-shame-fear model, Lewis’ LMR model involves three categories plotted on a triangle. But there are two key areas of difference. Lewis’ LMR describes communication styles, not cultural values or ethics. Also, plotting countries along the triangle’s perimeter makes the LMR model a two-dimensional analysis of culture. The guilt-shame-fear model offers locates a culture within the triangle’s body, showing the degree to which all three factors influence a culture.

4. Schrewer’s Big 3 of Morality

Cultural psychologist Richard Shweder speaks about the “moral themes” of autonomy, community, and divinity. As explained fully in this post, his model is very similar to guilt-shame-fear. Unfortunately Shweder’s model is not widely known.

Strengths of The Guilt-Fear-Shame Model

These four models are helpful and insight, but the cultural model of guilt-shame-fear has four distinct strengths.

One, the model is simple. The basic model can be explained in just a few minutes. There is no rocket-science or complex terms to understand, nor 6 categories to remember. Once a person understands the basic concept of guilt-shame-fear, they can begin to uncover new cultural realities for themselves.

Two, the model is informative. Since the cultural values of guilt, shame, and fear affect all of life, people start to see the dynamic everywhere. Guilt-shame-fear is a small key that can unlock big doors. The resulting “ah-ha moments” create euphoric learning moments, especially as people read the Bible.

Three, the model explains motives. Compared to other cultural models that describe how a culture functions, the guilt-shame-fear model explains why a culture functions the way it does. Instead of describing the external features of a culture, this model expands upon the internal values. Guilt-shame-fear provides a peek under the hood, so people can see the moral emotions and ethical values that drive cultural behaviors.

Four, the model is theological. The categories of guilt-shame-fear are theological realities, not just cultural descriptions. A conversation about guilt-shame-fear can naturally transition from culture to theology, creating an evangelistic opportunity. Guilt, shame, and fear relate to the core problem of humanity in Genesis 3. And the solutions of innocence, honor, and power are central features of the cross.

For these reasons, I believe guilt-shame-fear is a practical and helpful cultural model.

Read more posts in this series “Guilt-Shame-Fear: Revisited“.

There is a “Culture Compass” app for iPhone that is interesting and more beneficial than gimmicky. It could be a good introduction for short-term training to the concepts.

Thank you for this over view of culture models. It is a helpful way of thinking about and comparing the honor-shame model that you are promoting on your website with some other models.

I would like to make two suggestions. First, I think think we should consider using multiple models when analyzing culture. While many culture models overlap many of them also over emphasize either the internal cultural beliefs and value systems or the controlling social influences on the shaping of culture.

One should never discuss culture without also talking about the social realities that interact with cultural beliefs, values and other mental patterns. It is too easy to come to the conclusion that if humans think right or believe right or have the right attitudes that they can control their social behavior and social environment.

Likewise, one should never consider social realities without taking into account internal cultural assumptions. It is too easy to conclude that all cultural preferences are the result of social forces.

Second, I think your honor-shame model is an important theological model that leans in the direction of internal / mental patterns and emotions but it could be more effective in providing insight on human behavior if used with models that focus more on social structure (Mary Douglas’ Grid and Group theory) and social agency (Sherry Ortner’s Practice Theory). This would allow us to understand more deeply why some cultures are affected my the experience of guilt while others are more by shame and why people in some societies find them more effective ways of dealing with life’s social challenges than other people.

As Douglas has demonstrated many of the things we assume are theological issues are just as much reflections of social forces. For instance, many have written about the Reformation being as much about the collapse of hierarchy and the feudal system of Europe as it was about justification by faith and the priesthood of all believers.

Thanks,