The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Shaming

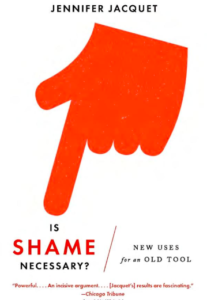

Shaming people can be a powerful tool for changing behavior and establishing norms. Jennifer Jacquet (Professor of Environmental Studies at New York University) in Is Shame Necessary?: New Uses for an Old Tool explains how people can shame selectively and effectively.

Shaming people can be a powerful tool for changing behavior and establishing norms. Jennifer Jacquet (Professor of Environmental Studies at New York University) in Is Shame Necessary?: New Uses for an Old Tool explains how people can shame selectively and effectively.

This post is a summary of her “7 habits of highly effective shaming.” Her suggestions focus on shaming large institutions such as governments and corporations. Keep in mind that these guidelines are not biblical principles per se. These principles do not apply to restorative shaming in personal relationships or small communities. The focus is on institutional shaming for systemic change.

- The audience should care. The social group that learns about the shameful behavior should also be the victim. If a company is polluting a town’s water supply, their shameful behavior should be exposed to those citizens to get them engaged. However, when the pizza man delivers the wrong pizza, that doesn’t affect other people—so there is no need to rant on Twitter, just call the company directly.

- The actual behavior should not be desired. There must be a big gap between reality and expectations. Shame is a strong solution. Like antibiotics, you don’t want to overuse it, or it loses its effect. So, shame should be reserved for extreme circumstances.

- Formal punishment should be absent. Shaming is a last resort, not a preferred option. You should first try to work through established protocol and systems as much as possible. But when legal recourse of intuitional structures does not allow justice, shame may be your best tool. For example, the financial industry received a $245 billion tax-payer bailout in 2008, then paid executives $20 billion bonuses and took lavish corporate retreats. There was nothing technically illegal with that behavior, so President Obama called them out as “shameful.” The U.N.’s Declaration on Human Rights has no legal teeth, so organizations like Human Rights Watch investigate and expose shameful behavior to enforce behavior.

- The transgressor should feel ashamed. The person should be sensitive to the group’s opinion. The source of the shaming is important. Shaming works when it comes from a member of the in-group. This works because the shamed do not want to be excluded from the group; they feel the threat of rejection. So, the people who are exposed must always have a chance to reintegrate into the group. The group must have a process of re-honoring the exposed.

- The audience should trust the shamer. People who shame must have credibility. If you expose someone, will others trust your report, or will they suspect your motives? The shame must be above reproach as well. An evangelical leader who says “morality matters” but gets caught cheating has no integrity. A government that lectures other countries on human rights loses credibility when they torture people.

- Shaming should have definite benefits. Our attention is limited, so frivolous shaming accomplishes nothing. When a problem is large scale, focus your intent on a specific incident. To limit fossil fuels, shaming 3 billion people won’t work, but you could expose the antics of oil producers to shape behavior. The various “Dirty Dozen” lists are examples of focused shaming.

- Implement strategically. Your method for shaming should be carefully considered. You must engage an audience. Sometimes the mere threat of shame suffices: a letter informing people that the names of all non-voters would be listed in the local paper had a significant increase in voter turnout. Other times you need a long-term plan: the ministry Open Doors publishes the “World Watch List,” an annual report of the top 50 countries where Christian persecution is most severe. This helps makes religious persecution a factor in international relations.

Conclusion

These 7 habits are not a moral justification for shaming. Rather, they are descriptions of how shaming can be an effective tool for changing behavior. In that regard, I find Jacquet’s list (and entire book) an insightful reflection on the positive uses of shame.

I believe your final comments are significant. But, in some respects it does beg the question since the moral justification for shaming is a primary and not a secondary issue. Shaming such as you have outlined seems to be a preferred tactic in this day of social media and no accountability. But if the one does the shaming is not also accountable to a recognized standard that exceeds relative cultural ones, who is to say it is justified? Perhaps, as seems so often to be the case on social media, it is really nothing more than an attempt to silence ones ideological opponents!

Agree with Dan. The 7 Habits assume that the Shamer and the Shamed agree that behavior X is shameful. That is true and shaming can be effective when the Shamed was previously hiding the behavior, but it is not true when the Shamed was championing viewpoint X publicly and ideologically as the basis for behavior X. To use the 7 Habits against any particular viewpoint (racism, Christian faith, whatever), one must first make a moral judgment of that viewpoint, declaring it shameful. I can’t help wondering what Jacquet says about the basis for those moral judgments.