5 Lessons I Learned From Being a Terrible Patron

Rich (B.Th) has worked in the Arab world for 6 years and is researching patronage in Arabic language, culture and theology.

Arabs look to community leaders to help them, including managers, fathers, businessmen, celebrities and teachers. My university students expected me to help them with various life issues or mediate discussions with other lecturers. I would usually refuse saying it wasn’t my place to intervene.

My students didn’t have the same scruples. They’d generously offer me help from well-connected people in their families on a range of things from getting paperwork done, to hiring cars, to meeting influential people.

My students didn’t have the same scruples. They’d generously offer me help from well-connected people in their families on a range of things from getting paperwork done, to hiring cars, to meeting influential people.

1. Patrons care for their flock

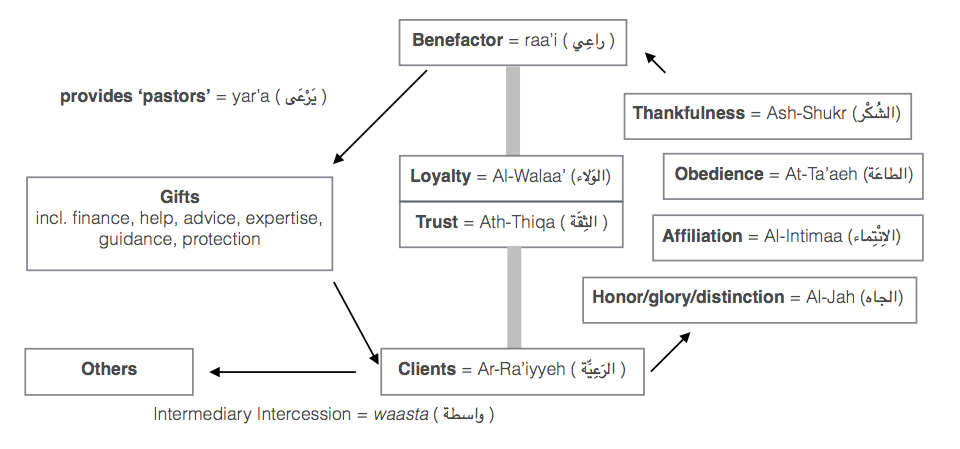

Arabs expect people with power, resources or connections to help those less fortunate. God blessed them to bless others. The Arabic for patron— raai—means “shepherd,” and the clients they care for are called “their flock.”

Some Arab patrons become someone’s kafeel. This means they guarantee to use their honourable status to protect them, pay debts, speak on their behalf when accused, and to represent them in all disputes. Based on my survey of 200 Arabs, 95% agree that “patronage plays a role in my life.”

2. Ingratitude shames

Arabs quote the proverb, “If you give to a generous person, you’ll own them, but if you give to a depraved person, they’ll rebel against you.” Good people repay favours with loyalty and honor. My students repay me by obeying me or honouring my teaching skills before other teachers.

In the proverb, people who receive but then don’t return honour are “depraved.” Ingratitude is one of the worst traits in the Arab worldview. The failure to reciprocate shames those who gave, and this destroys relationships.

Sadly, I now realise I often shamed students by asking them to help me with something they couldn’t. They felt ungrateful and depraved since they could not return help. The shame caused them to skip classes to hide from me.

3. Asking for help honours

I now ask for help indirectly to protect my students’ honour. If they can, they offer to help. If they can’t, they specifically haven’t let me down. They usually do the same to me.

4. Showing gratitude honours

I’ve also been struck by how greatly Arabs express their gratefulness for gifts or favours. Its so honouring of others’ generosity, and the reciprocity strengthens relationships.

5. Patonage and the gospel

Reciprocal favours permeated relationships in antiquity (see John Barclay, Paul and the Gift). The system of reciprocal giving was called “grace.” Likewise, ingratitude was seen as one of the worst traits.I’ve found it very powerful to explain these aspects of the gospel to Arabs.

Paul says God “made the world and everything in it…he himself gives everyone life and breath and everything else….so that they would seek him” (Acts 17:25). The problem is that mankind repaid God’s generosity with ingratitude. We neither glorified God not gave thanks to him. Instead we rebelled, dishonouring God. We broke our patron-client relationship. This realisation causes great shame in Arabs.

Wonderfully, God, who gives to the ungrateful and the evil (Lk. 6:35), responds incongruously to our ingratitude. He gives us the single and greatest gift possible, his beloved son’s life.

When we trust in Jesus, he becomes our “kafeel.” He guarantees us. He pays our debt. He speaks on our behalf. He gives us His honour. He re-connects us with his father and other believers.

Brings new meaning to Scriptures that refer to a shepherd, doesn’t it?

The original audiences of such passages, such as Psalm 23 and John 10, would understand the idiom, regardless of age or status in the community. I’m afraid that may not be true in our modern day. The scholarly and well-educated may grasp that there are other ideas or ways to understand Scriptural principles or that the Bible wasn’t written in English (should be obvious, but you may be surprised!), but most westerners in the pews only know what the pastor tells them about the Bible. Oh sure, there are Bible studies, but the methodologies employed have more to do with ‘what does it mean to ME?’ or ‘how does it apply to ME?’ as opposed to grappling with the Greek, Hebrew or the idioms of a 4,000 year old culture. If the training (theological, as well as appreciating other cultures) of church leaders is lacking, then with what tools or to what end is the church being led?

If God’s offer of “grace” inherently carries with it the idea of reciprocity, then it is easy to understand why many of my eastern friends consider that my western idea of grace(something freely given and without strings) is a ‘cheap grace.’ Reciprocity does not necessarily convey equality (we, westerners are adamantly egalitarian), but it most certainly conveys allegiance to the patron. Absent reciprocity, the recipient may continue his/her life as if the gift (grace/salvation/forgiveness, etc.) were from last year’s Christmas gift exchange.

I trust that your posts and the discussions will enlarge the church’s tent and so draw men/women into it.

Really love this post.

Many of your posts help me to better understand some of the similar social dynamics in biblical times. Thanks.

Rich, thank you for this excellent post. You not only highlighted the social elements of patronage, but also how the Gospel is expressed in patronage terms in the Bible. You’ve expanded another facet of the Gospel and helped us to see it better in relational terms. I think one danger in having a one-faceted grasp of the Gospel in exclusively legal terms, is that we can think of the Gospel as a government entitlement program. It’s often not the reconciled relationship with our Creator that we emphasize, but the benefits that we get–kind of a spiritual welfare program. When we expand our view of the Gospel in the biblical terms of relationship and power, our view of God, of Jesus, of grace expands and the result is indeed praise and gratitude. Thank you for helping us along in this journey!

I am very grateful for Jayson’s bringing us this topic.

It seems that I have ‘come across’ people who have emphasised shame verses guilt many times over the years, but not taken the time to try to find out what it all really means. This time I have, over and beyond what Jayson shares above, and it is being an interesting journey.

I have some questions in my mind. One is a basic ‘evaluation’ question. ‘Are shame cultures OK’, if you like? Does Christ take us towards guilt cultures? My suspicion is very much the latter. But, I have not really found people who say that directly.

Guilt, it seems, is a distancing of one’s reputation from one ‘self’. I am guilty of a bad act, instead of ‘I am bad’. Is that not liberating?

I wonder also how this relates to exorcism. Exorcism is the removal of a demon. Jesus engaged in a lot of this. Telling someone that there trouble is due to a demon seems to be a way of taking them towards a guilt culture. Instead of ‘I am a thief’, it is ‘I have a demon of stealing in me, who needs to be removed’.

I think that ‘forgiveness’, if I understand rightly, is about being in a guilt culture. That enables ‘sin’ to be something that is seperate from ‘me’, so that it can be removed. In shame cultures, there is then ‘no forgiveness’.

I could add the whole mechanics of shame-cultures, the enormous respect given to hierarchy, the orientation to acquisition of power, i.e. money, to be displayed.