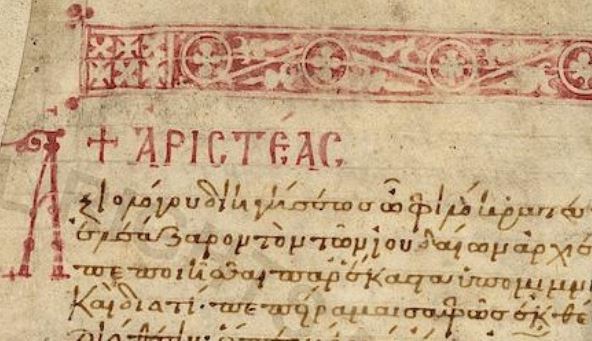

Honor and Shame in Letter of Aristeas

Letter of Aristeas is a second-century BC “historical letter” explaining the composition of the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Old Testament, i.e., LXX) by Jews in Alexandria. Honor and shame are prominent motifs in the story.

The Plot

The story begins with the Ptolemaic king in Alexandria requesting a copy of the Jewish Law for his library. He sends his head librarian, bearing extravagant gifts for the Jerusalem temple, to the Jerusalem High Priest named Eleazar, who gladly complies and sends 72 Jewish elders to Alexandria to complete the Greek translation of Torah. When the 72 elders arrive in Alexandria, they enjoy a lavish feast with the king and display their wisdom. Then they complete the divine translation, to the praise of all. The Letter of Aristeas emphasizes the authority of the Alexandrine translation and portrays Alexandrine Jews as assimilated into Hellenistic culture.

This story from the intertestamental period provides cultural background for the New Testament context, especially regarding honor and shame. In terms of vocabulary, “honor” appears 20 times, “glory” 26x, and “worthy” 20x. The author uses heroic characterization to communicate honor-shame values. The narrator portrays the main characters—Ptolemaios the king, Eleazar the high priest, and the 72 elders—are pious, philanthropic, worthy, and glorious. Their honorable reputation confers authority upon the translation they collaborated to produce.

Ptolemaios, the Hellenistic King

The Ptolemaic king functions as the Gentile protector/savior of the Jewish people. In the opening scene, he liberates tens of thousands of enslaved Jews from captivity (17–19). With imagery from Exodus, the author interprets this action as an act of worship—an honorable person giving thanks/glory to God. The king’s advisor says, “It is worthy of your magnanimity to offer the release of these [Jewish] men as a thank-offering to the Most High God. For you are highly honored by the Lord of all, and have been glorified beyond your ancestors, so if you make such a great thank-offering, it is befitting of you” (19).

The generous king establishes his glory by providing for his subjects. Or more accurately, the king, as a broker, mediates God’s blessings to people. “For as God showers blessings upon all men, so you too, in imitation of him, are a benefactor to your subjects” (281). This king of Egypt is the antitype of Pharaoh. Instead of oppressing Israel and defying God, he honors the Jews and their God. The ideal king dispenses and receives honors.

Ptolemaios also provides gifts to furnish the Jerusalem temple and then oversees the public translation/reading of the Law. These elements—liberation in Egypt, temple construction, law giving—cast Ptolemy as the “new Moses.” The translation event serves as a “new Exodus” for God’s people in Egypt. However, whereas the original exodus-event and law-giving distinguished Israel from Gentile nations, this new exodus and law (i.e., LXX) integrate Jews with Gentiles. Ptolemaios, as the ideal king, unites the people under his realm, creating a harmonious society (37). The noble king rescues, honors, and provides gifts unto the people of God. The New Testament employs a similar royal ideology for Jesus.

This ideal king also seeks wisdom, in the way of Solomon. In particular, he pursues the path to true honor. At the royal feast, the king asks each of the 72 Jewish elders a philosophical question, many of which pertain to honor (cf. 226f):

- How can we avoid doing anything unworthy of ourselves?

- How can a man maintain the glory he received?

- To whom must a man show love-of-honor?

- To whom must a man show favor?

- How can a man, after a misstep, recover once more the same degree of glory?

- What is the greatest form of glory?

- How can a man pay his parents the debt of gratitude which they are worthy of?

- What human is worthy of being marveled at?

The king desires to embody and display true glory.

The Jewish elders are quick to praise the Gentile king, particularly for his generosity, benevolence, and philanthropy—all virtues of honor. “You are distinguished … by the outstanding glory of your government and our wealth.” Then, “by your righteous steering in all things have furnished for yourself an everlasting glory” (290-91). Such Messianic/David language for a Gentile king, albeit pragmatic for currying social favor with the Hellenistic overlords, contrasts with the Judean Jews who sought liberation from pagan rulers and glory unto themselves. For the Jews in Alexandria, God has already instilled a noble (Gentile) king under whom the Jews prosper and experience an exodus-like status. However, this new exodus is not from Egypt, but in Egypt.

Eleazar the High Priest

The narrative introduces the Jerusalem high priest Eleazar as a high priest “whose conduct and glory have won him preeminent-honor in the eyes of both citizens and others alike” (3). His interpretation of the Law brought the greatest benefits to many people (3), just as the Egyptian king “bestowed great and unexpected benefits upon [Jewish] citizens in many ways” (44).

The Jewish high priest responds positively to the Egyptian king’s offer of “friendship,” a technical phrase referring to their mutually-beneficial alliance. Both sides act in noble and generous ways, affirming the honor of the other party, and, thus, act in a manner “worthy” of the relationship (40-41, 179). Such love and friendship refer to mutual honoring through diplomatic protocols. The two leaders allow each other to provide benefits and, thus, appear as magnanimous co-patrons of the sacred translation project.

The narrator describes the Jerusalem temple system (83f), in which everything is done with “fear and also in a manner worthy of great divinity” (95). This includes the priest Eleazar “with both his vestments and glory” (96). The high priest embodied divine glory. “Now on his head he has what is called the tiara, but on this the inimitable turban, the royal diadem having the name of God in relief on the front in the middle in holy characters on a golden leaf, ineffable in glory. The wearer is considered worthy of wearing these vestments during the public-services” (98). As the official head of the Jerusalem Temple and Jewish people, Eleazar embodies honor in both religious and diplomatic contexts.

72 Elders/Translators

The 72 elders, six from each of the 12 tribes, are men of great knowledge and honor. They are supremely qualified for the task, in large part because of their noble status confirmed in many ways. “For the chief-priest selected men of the best merit and of excellent discipline due to the distinction of their parentage; they had not only mastered the Judean literature, but instead had even made a serious study of the Hellenic literature. And for this reason, they were well qualified for being the elders, and brought it to fruition as occasion demanded. … And they were, one and all, worthy of their leader and his outstanding excellence” (121-22).

Upon their arrival in Alexandria, the Ptolemaic king breaks official protocol to confer extraordinary honors upon the Judean delegation. For they, and the one who sent them (Eleazar), were worthy of great honor and high regard (175). The king makes a point of “not omitting any form of honor being done to these men” (183). The king recognizes their preeminent status with verbal affirmations and then public feasts. Akin to Esther, the Jewish nobles dine luxuriously in the king’s court.

The longest section of the narrative involves the elders’ replies to the king’s impromptu dinner questions. The elders appear as wise philosophers, affirming the king’s honor and displaying their own. A few examples illustrate their reflections on true honor.

- Always have an eye to your glory and your prominence [as the king], so that you may say and think what is consistent with it, knowing that all your subjects also have you in mind and utter things about you. (218)

- By practicing goodwill to all humans and by forming friendships, you would owe no obligation to anyone. But to have gratitude with all humans, and to receive a handsome gift from God—this is one of the strongest gift. (225).

- It is a man’s duty to show a love-of-honor toward those who are amicably disposed to us. That is the overall opinion. But I think that we must show the same keen love-of-honor to our opponents, so that in this manner, we may convert them to what is proper and fitting for them. (227)

- [The greatest form of glory is] Honoring God. But this is not done with gifts nor sacrifices; instead, it is done with a soul that is clean and of a disposition that is sacred, since everything is furnished by God, and administered in accordance with his wish. (234)

At the end of each day’s feast, the king praises, congratulates, compliments, and applauds the Jewish elders. He declares that they are greater than the philosophers (235) and their mere presence is the “greatest good-thing” (293). Like Daniel and Mordecai, they enjoy royal honors for their divine insights.

When the Jewish elders compose the translation, they wash their hands as evidence that they have no evil (306). Other figures had attempted to translate the Torah into Greek but were smitten with illnesses because of their inadequacy. However, the text produced by the 72 elders is publicly read, admired, and accepted as authoritative by the local Jewish community (308-10). Among the various Greek translations available to Jews is Diaspora. This text gets “canonized” because it was “made beautifully and sacredly” (310).

The elders even exit the narrative with great honor. The king promised that if the elders returned to Alexandria, he would, “as was proper, treat them as friends, and they would receive the greatest gifts [of liberal hospitality] from him” (318). In a final display of mutual honor, the king treated the elders magnificently with fine gifts as they departed for Jerusalem.

Why Honor?

Why does the author Eristeas so emphatically foreground the honor of every character in the story? Even the Egyptian artisans who carved objects for the Jerusalem temple “make it a love-of-honor to complete everything in a way worthy of the king’s majesty.” Why is honor so pivotal in this narrative?

In collectivistic contexts, people equate messages with their messengers. Authority is social. The honor and nobility of the king, priest, and 72 elders bestow authority upon the text they produce. Their sacred honor is transferred to the work they produce. Only divine figures could produce a text so “solemn and of divine origin” (313).

The patrons are worthy of honor for their many gifts, chief of which is this translation. And the gift itself is worthy of honor. The Jewish multitudes are amazed by its words and request a copy for their own community (just as the Israelites confirmed and received Torah at Sinai, cf. Ex 19:7–8). Even the Gentile king asks “for great care to be taken of the books and to keep them pure” (317). The king had earlier granted the same reverence to the Hebrew scriptures. When the elders arrived, they unveiled the marvelous parchments with Torah in gold lettering. The king paused, then bowed seven times before the oracles of God (176–77). By the end of the story, this Alexandrian Greek translation merits the same honor as the Hebrew original. This LXX can be faithfully received, read, and obeyed by the community as God’s sacred and authoritative text.

When I read a story like this, I get the sense that true or real life is social, outward.

I wonder is the love-of-honor life only public or social? Does self-reflection and inner consciousness play a role in this love-of-honor?