When to Shame? When to Honor?

When should we honor (or shame) someone?

This question is complex and has many facets. However, the book Economies of Esteem (OUP, 2004) offers interesting insight into “esteem equilibrium” (pages 126-29). As an economic theory, their model is descriptive, not prescriptive. However, I think their insight can help us in the areas of moral and community formation. The authors are professors of philosophy and economics, so their explanation is technical. Here is my summary.

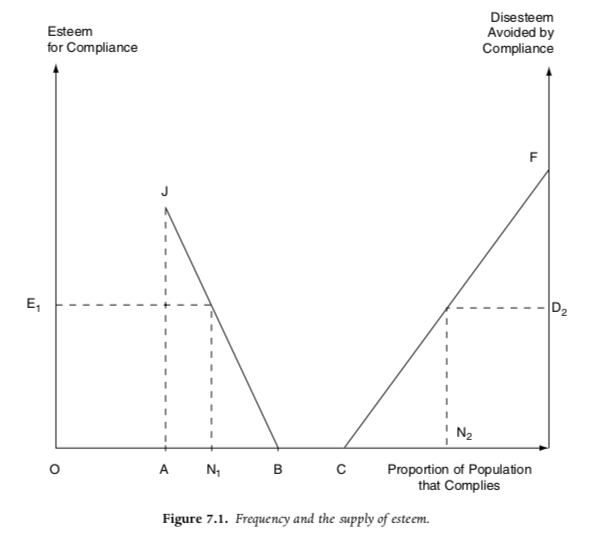

Basically, whether we esteem or disesteem (their terms for honor or shame) a certain behavior depends on the rate of compliance in the group. So, if I do something virtuous that nobody else is doing, you will likely honor me for such unique behavior. However, if everybody already engages in that behavior, I do not receive honor simply for doing what others already do.

However, if most people already perform the positive behavior (i.e., “a high rate of compliance”), then I do not lauded for engaging in the behavior; though I do get shamed for not keeping the norm. In situations with high rates of compliance, my ethical motivation is the avoidance of shame, not the earning of honor. In short, we honor people for something exceptional, and we shame people for not doing what is standard. (See their Figure 7.1 below, from page 128.)

The authors present recycling as an example of this phenomenon. In the 1970s, waste recycling was rare. The practice took effort, and so it required a (admirable) commitment to the environment. Now, in 2020, recycling is a common and easy practice. “Once normal, however, it no longer reflects any particular credit on its practitioners, so positive esteem evaporates. At the same time, those who don’t recycle now begin to become conspicuous” (p. 127). Thus, it becomes embarrassing to not recycle.

In the New Testament, consider how Paul honors those who sacrificially travel (Phil 2:29) or host others (Rom 16). These were extraordinary behaviors that merit recognition. Then consider examples of people whom Paul shamed—fornicators (1 Cor 5) or Gentile-avoiders (Peter in Gal 2). Their behavior deviated from the normal expectation of Christian behavior, and so it had to be exposed (with the ultimate aim of restoration).

That is the basic idea. What are your thoughts? Share below!

It seems to me that God honors obedience whether it is normal or exceptional. We should be more like God.

Thanks for sharing this intriguing summary of the book. It reminds me of the honor/shame dynamic we find in the ‘Good’ Samaritan story and the way it has been popularized. The concept of ‘Good Samaritan’ has entered into public life. It is common for local TV news programs to laud the behavior of a ‘Good Samaritan’ for doing some deed for someone else, often at great sacrifice. I’ve always found it interesting at the contrast of commentary. The broadcasters make a big deal of this ‘exceptional’ behavior, but invariably, when interviewing the ‘good samaritan’, this person will say, “Oh, I just did what anyone would do in that situation.” To me this points to the inaccuracy of the title this story is given. When we label the Samaritan ‘good’ we are doing what the TV broadcasters are doing, that is, we are exceptionalizing behavior which Jesus expects to be normal, i.e., what anyone should do. Loving neighbors, near or distant, is expected for the people of God.

Thanks for this very practical consideration.

I recognize that the question of when and how to shame or honor can result in positive change or negative antagonism and worse. I would be interested to see what other Christians have written that may give careful attention to this matter.

Interesting analysis. I wonder if this will translate to the mask-wearing conflict in the US? I currently live in Japan where this practice is standard. Not excited about returning to states amidst this conflict.

Your post reminds me when Jesus asks, “If you love those who love you, what credit is that to you?”

Too often we honour others (and ourselves) for merely doing what’s common.

Yet Jesus compels our love and service to be extra-ordinary, even unto our enemies. That is truly honourable.

This seems a too simplistic description of honor (esteem) and shame (disesteem) . They are much more powerful and emotional. I’m not sure, either, that these should be represented as a just like two tanks of water: one high, one low, where one goes up when the other is down., as if we have a limited amount of both combined together. Perhaps from economic viewpoints this works, but not in spirituality It’s useful to a certain point only.

Good point for sure, Jim. You are right to mention this, as honor and shame are quite complex and work in many (perhaps contradictory) ways, as they as rather elusive and abstract realities. Their book, to be fair, offers a sophisticated economic argument for honor/esteem as a transacted commodity. This insight posted here was a summary of 2-pages, not their book. I thought it was a helpful paradigm for observing how (dis)honor may function.

This phenomenon is true and today it is driven by what social media figures deem honorable and shameful (or popular and unpopular). The question is how can followers of Christ influence these factors in light of the many destructive trends on social media. How can we trend people towards truly honorable things.