3 In 1: Integrating Guilt, Shame, and Fear

People often voice the concern that reducing cultures down to “guilt,” “shame,” or “fear” is oversimplifying reality—“Aren’t cultures a combination of these factors?” Most certainly. Cultures are too complex to be isolated into just three boxes. These are not three distinct categories, but factors that influence every culture to some shape. Guilt, shame, and fear are present in every person and every culture, but to differing degrees. The complexity and richness of human culture is not like Neapolitan ice cream with three separated flavors. This post explains how the three culture types overlap and integrate.

The phrase “guilt-innocence culture” is like the phrase “right-handed person.” When I say that I am right-handed, it does not mean I never use or my left hand (or don’t have a left hand!). The phrase simply indicates my primary preference. The categories are like caricatures—they highlight the most distinctive features to allow for easy identification.

Authors have used various images explain how the three dynamics interact and overlap in every culture. Guilt, shame, and fear are like:

- the primary colors that artists use to hundreds of subtle hues. (Muller, Honor & Shame, 16)

- a swan formation, in which the strongest swan leads but the others follow closely in line. (Hegeman, EMQ, 2010)

- a strand of interwoven threads, each unique but still interrelated with the others.

- the corners on a triangle, with each cultural group being located somewhere within the triangle depending on which corner tugs the strongest. (The 3D Gospel, 16)

3 Integrated Systems

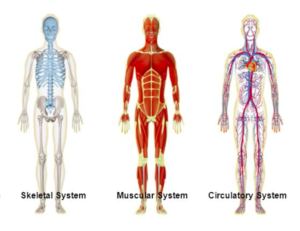

Guilt, shame, and fear are three socio-moral systems that work together in given culture. This can be compared to the human body, which consists of a skeletal, muscular, and circulatory system. Of course, nobody with common sense would conclude from this picture, “Scientists say there are three type of people in the world: some have a skeleton, others have muscles, and the rest have a circulatory system.” Rather, the three systems are isolated from one another for understanding and analysis. But as everyone knows, the three systems are closely interrelated, and even inseparable in our actual, real-life bodies.

The Ephesian Riot (Acts 19)

The story of the Ephesian riot in Acts 19 is a narrative example of how guilt, shame and fear interplay.

Paul taught boldly about the Kingdom of God in Ephesus for two years. “God did extraordinary miracles through Paul, so that when the handkerchiefs or aprons that had touched his skin were brought to the sick, their diseases left them, and the evil spirits came out of them” (19:11–12). The power of God was evident through the miraculous healings from sickness and evil spirits. People were released from Satanic bondage. Then the seven sons of Sceva the high priest come visit Ephesus. As exorcists, they seek to appropriate God’s power over evil spirits, but their plan backfires. The evil spirit ignores their authority and overpowers them.

These fear-power incident leads to an honor-shame response. The exorcists run into public naked and wounded. Their spiritual weakness becomes a social disgrace. Plus God is honored through the incident—“When this became known to all residents of Ephesus, both Jews and Greeks, everyone was awestruck; and the name of the Lord Jesus was praised” (19:17). Many of those believers transfer their allegiance from occult practices to the living God. Burning the magic books publically values and honors God. (This explains why Luke notes the enormous financial value of the lost goods). God’s victory in the spiritual world leads to public honor.

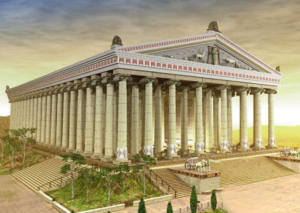

Ephesians was famous in the ancient world as a center in magical practices. The temple Artemis was the religious epicenter of religion in Ephesus. The complex had 127 towering columns and measured 450 feet long, 225 feet wide and 60 feet high. One ancient historian distinguished it as the most impressive of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was renown throughout the world for its splendor.

Ephesians was famous in the ancient world as a center in magical practices. The temple Artemis was the religious epicenter of religion in Ephesus. The complex had 127 towering columns and measured 450 feet long, 225 feet wide and 60 feet high. One ancient historian distinguished it as the most impressive of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. It was renown throughout the world for its splendor.

Over time Paul’s ministry affects the economy centered about the temple. As local citizens turn away from false gods, they no longer purchase the silver shrines of Artemis for spiritual protection. As believers redefine the fear-power elements of their culture, there are obvious honor-shame implications. The silversmith Demetrius rallies the crowds by appealing to reputation in several ways. Because of Paul’s ministry, the local silversmith says, “this trade of ours may come into disrepute but also that the temple of the great goddess Artemis will be scorned, and she will be deprived of her majesty that brought all Asia and the world to worship her” (19:28, emphasis added). Artemis’ status is under threat , along with their own socio-economic status. So they reaffirm her majestic status, shouting for hours “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!”

The town clerk brings order to the unruly crowds, first by reaffirming the honor of Artemis, then by noting that no one actually shamed the name of Artemis. For these reasons, there was no reason to be upset. The town clerk then appeals to the guilt-innocence aspects of the culture to resolve the public disgrace (honor-shame) of the local god (fear-power).

If therefore Demetrius and the artisans with him have a complaint against anyone, the courts are open, and there are proconsuls; let them bring charges there against one another. If there is anything further you want to know, it must be settled in the regular assembly (19:38–39).

Their problem must be resolved through the official courts, lest they be indicted for breaking the law themselves. The story of Acts 19 illustrates how guilt, shame, and fear are woven together.

Read more posts in this series “Guilt-Shame-Fear: Revisited“. Also see the post “1 Gospel for Guilt, Shame, and Fear Cultures” by Jackson Wu.

The passage in Acts 19 probably also represents a “magic oriented” culture, so the use of a handkerchief (or elsewhere, Peter’s shadow) was not that surprising.

My wife and I worked as Bible translators in Papua New Guinea for many years. Certainly “shame” was easily translated and known; “guilt” was much more difficult.

with fear guilt and shame, i wonder how justice mercy grace and forgiveness shape a person verses a culture?

Thank you .. very helpful. I’m becoming aware of the 3D more and more and expect to incorporate it into missions prep teaching.

Very interesting, I never thought about the Ephesus riot in an honor-shame context. Thank you for another encouraging post.