The Real Problem with Evil and Suffering

Evil and suffering are a P.R. nightmare for God. “How could there be a God when … ?”

You’ve heard the arguments. Apparently, God is not being God, and this requires some explanation. The answer to the question of why God permits evil is called “theodicy.” Theodicy (theos + dikē) defends God’s righteousness, or justifies God, in the face of evil.

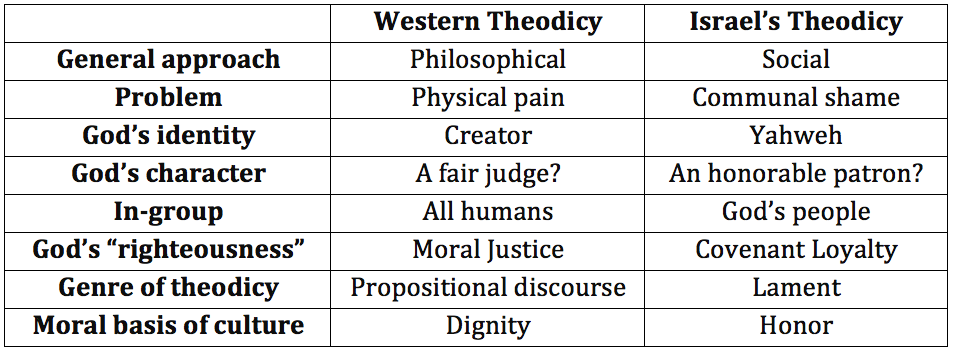

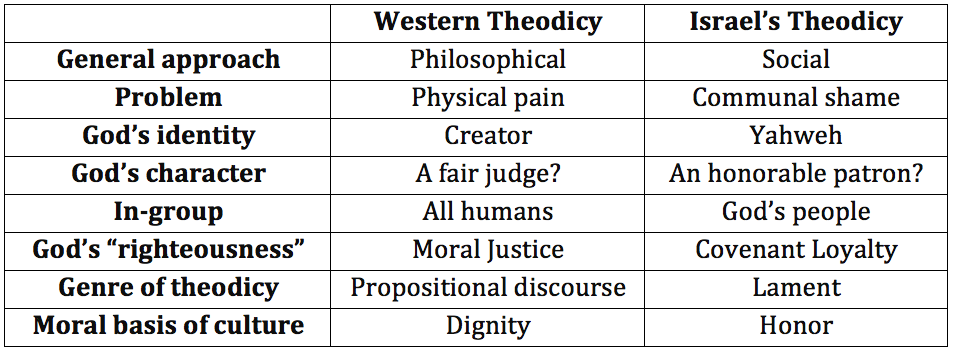

Many excellent apologetics books explain evil for modern Westerners. However, their “philosophical” theodicy differs significantly from Israel’s “social” theodicy. Comparing the two theodicies can help us read the Bible on its terms and reveals the real problem faced by humanity.

Here are 5 general differences between contemporary theodicy and Old Testament theodicy.

In contrast, contemporary theodicy offers a cognitive and abstract explanation. Today’s thinkers treat the suffering of humanity as a philosophical problem solved by intellectual reasoning. The answer to suffering and evil is a logically plausible explanation. The 1710 publication by German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz coined the term “theodicy.” His subtitle reflects the philosophical underpinnings of modern theodicies— Theodicy: Essays on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil.

But, many Psalms assume otherwise—the success and blessings of Gentile enemies confounds Israel; the shame and punishment of enemies actually proves God is righteous. Israel is not concerned about humanity as a whole, but her own kin. The question of Israel’s theodicy is: Why do we suffer exile and disgrace? Why does our king not reign victoriously?

The following diagram summarizes these differences.

Israel’s social theodicy has significant implications for hermeneutics, atonement, and missional engagement. What applications do you see in Israel’s social theodicy?

This post is from my paper “‘From Shame to Glory!’: Israel’s Social Approach to Theodicy,” to be presented this weekend at the Evangelical Theological Society meeting in Columbia, S.C. If you are attending, let’s connect!

You’ve heard the arguments. Apparently, God is not being God, and this requires some explanation. The answer to the question of why God permits evil is called “theodicy.” Theodicy (theos + dikē) defends God’s righteousness, or justifies God, in the face of evil.

Many excellent apologetics books explain evil for modern Westerners. However, their “philosophical” theodicy differs significantly from Israel’s “social” theodicy. Comparing the two theodicies can help us read the Bible on its terms and reveals the real problem faced by humanity.

Here are 5 general differences between contemporary theodicy and Old Testament theodicy.

-

1. Solution: Exaltation vs. Explanation

In contrast, contemporary theodicy offers a cognitive and abstract explanation. Today’s thinkers treat the suffering of humanity as a philosophical problem solved by intellectual reasoning. The answer to suffering and evil is a logically plausible explanation. The 1710 publication by German philosopher Gottfried Leibniz coined the term “theodicy.” His subtitle reflects the philosophical underpinnings of modern theodicies— Theodicy: Essays on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil.

-

2. In-Group: God’s People vs. All People

But, many Psalms assume otherwise—the success and blessings of Gentile enemies confounds Israel; the shame and punishment of enemies actually proves God is righteous. Israel is not concerned about humanity as a whole, but her own kin. The question of Israel’s theodicy is: Why do we suffer exile and disgrace? Why does our king not reign victoriously?

-

3. Problem: Social vs. Physical

-

4. God: Yahweh vs. Creator

-

5. Genre: Lament vs. Treatise

The following diagram summarizes these differences.

Israel’s social theodicy has significant implications for hermeneutics, atonement, and missional engagement. What applications do you see in Israel’s social theodicy?

This post is from my paper “‘From Shame to Glory!’: Israel’s Social Approach to Theodicy,” to be presented this weekend at the Evangelical Theological Society meeting in Columbia, S.C. If you are attending, let’s connect!

I’ve never felt comfortable with modern explanations of the question why a good God allows suffering. I don’t think God owes us an explanation and I don’t see that He gives us one. He didn’t give Job an explanation; He reminded Job of who God is and who Job is; however, God’s righteousness was attested in His actions to Job. That seems to be the answer. Jesus shared in our suffering. That’s better than an explanation! Habbakuk poses the question to the LORD, “Why then do you tolerate the treacherous?” God’s answer: the righteous will live by his faith. Twice in Romans Paul rhetorically questions God’s justice (3:8; 9:20) and both times he leaves the question unanswered. During the exile Ezekiel records, “Yet, O house of Israel, you say, ‘The way of the Lord is not just.’ But I will judge each of you according to his own ways” (Eze 33:20). I like the way, Jayson, that you bring up the relational and covenantal considerations. That seems to be the approach that God gives us. When we want an explanation, we turn the focus on the wrong person!

Thanks Sean for the insighful and pastoral reflection. Those are great ideas, and biblical passages.

There may be some sense in which God “owes” His creatures nothing – I do hear the sentiment regularly.

But I don’t think this is either a complete theology, nor a logically consistent one. So, here is an alternative perspective which I think is fully biblical, but am open to correction on: God “owes” whatever He promises to give.

At this point I won’t go into all the rest that this entails, because a denial of this premise pretty well negates anything that would follow, and it seems to me, would make Him of a capricious character, therefore untrustworthy.

So, what do you think?

Thanks,

Lynn

I agree, Lynn, that what you said is the “other side of the coin” per se. This is exactly the kind of argumentation we see over and over in the Old Testament, specifically, (Abraham, Moses, prophets), and which Jayson highlights in the passages where YHWH is the suzerain king, the divine patron, who is committed to protecting and dignifying his people. This is the covenant that YHWH makes with Israel in Deuteronomy and so the prophets point out that Israel broke the covenant, thus the LORD will destroy them and take them into shameful exile. But as you say, time and time again the same prophets remind God of his promises and God reminds them that He will indeed keep those promises–and I think we all agree that He did! Thanks for making that point. I’d love to hear you elaborate further.

Yes Lynn, I think you are getting at something key here. God is not an absent Deistic father who abandoned all responsibility after creation, but he obligated himself to certain actions when initiating a covenant with Abraham (then Israel, then Moses, and now new covenant). Though voluntarily, God gave his word to save, and he is now “honor-bound” to do so, lest be considered unfaithful or too weak to keep his promises. So yes, God does “owe” us something. But to be clear, that has absolutely nothing to do with us (as if we gave something to God and he is indebted to us), but rather is because committed himself to save the human family. That would be my approach, which naturally leads to Israel social theodicy for those moments God is not fulfilling those self-imposed obligations.

It looks like Sean is thinking similiarly. Is that what you had in mind as well?

Yes, and Yes…to what both Sean and you say in your replies. My main point is that God is (to apply the title of your book) 3-D, and so He deals with us in all the dimensions He has given us. I don’t see in Scripture that He avoids or fails to give rational explanations in the face of “The Problem of Pain” (theodicy), rather that He knows that rational explanations will only go so far to address our needs, so He knows that relational comfort (with Himself and with others) is necessary as a 3-D “answer.”

This is a key reason why C.S. Lewis moved on from writing his directly apologetic works (full of “reasonable explanations”) to the more fully-orbed apologetic that’s presented in the Narnian Chronicles. I am editing his Chronicles for a translation project and just completed The Magician’s Nephew, which gives a wonderful and extended example of the way God “answers” our own grief by showing that He feels it (in this context, Digory’s grief for his deathly-sick mother) and suffers “if possible even more than Digory.” Digory is comforted at the most crucial times in his doubt and temptations by remembering the huge, pure, tears of Aslan. It’s Jesus weeping over Lazarus’ death, and over Jerusalem, and over all of us at Gethsemene.

So, I do see God giving us rational explanations in the face of evil (they are there in Job, Paul, etc. it seems to me), but knowing they are not enough, especially as a primary trait in certain cultures (ANE, for example), and even for people of any culture at certain times. He gives what is needed, because He honors what He has put within us.

Is there a perceived gap between God’s sovereignty in a situation of pain and loss and that of his promise here? God’s character is logically consistent in allowing suffering without owing a completely rational explanation nor the complete human realisation of a divine promise. Ultimately we will find a reconciliation of suffering and promise, but we cannot demand that God should keep his promise in our way in our timing, since he will do so in his way that brings him glory. This, the mystery of human suffering, means that wanton pursuits of rational explanations for it are in vain. Should we seek God in prayer and reason for his promise? Yes, but humbly as did Abraham, recognising that we are but dust and ashes on our own. Demanding or expecting God to continue to uphold a promise that is his means we haven’t understood the redemption that underlies it. As Peter said the main matter is to continue to do good in the face of suffering, rather than to try and work out why that suffering is taking place, a matter that will be revealed in due course. God is still a good God in the face of it all can be held to consistently. He would not be capricious for withholding certain levels of explanation, he would only be God!

I would agree with most of what you’ve said, Nicholas.

I think it helps to make some of the statements more universally applicable to all situations and depth of devotion. So, here’s a stab at that. See what you think…

a) “…we cannot demand that God should keep his promise in our way in our timing,”

LB: a suggested qualifier: “we cannot demand that God should keep his promise in any way that would mean violating His character.”

This is to allow for those “ways and times” when “our way” is, in fact, aligned with His, as well as when they are not. For a devoted follower, our ways and/or timing will often be in alignment. Some people seem to assume that “our way” and “our timing” are always contrary to God’s.)

b) “since he will do so in his way that brings him glory.”

LB: Yes, he will definitely do things his way, and that way will bring him glory. But God accomplishes more objectives when he does things than giving himself glory. However high we put this particular thing on the scale of achievements (top?), it is still not the sole achievement. So I think we need to find words to point that out – especially in the context of grief (theodicy) – that some of those benefits of God’s way and timing are the fulfillment of the person/people suffering, and we could probably add: all creation.

c) “This…means that wanton pursuits of rational explanations for it are in vain.”

LB: By definition, “wanton pursuits” are sinful, so we can’t expect God to honor them. If we change the word wanton to “bold” or “confident” or “diligent” or other morally untainted qualifiers, then I do think we have to remove “vain” – and then we can conclude that he will honor them.

But the point is that we should not assume that a person’s expectations – or even demands – for rational explanations are necessarily sinful. That’s why I wrote above that we are multi-dimensional beings, God knows all those dimensions, and he provides each one of us with satisfactory “answers” based on the full complexity of our own personalities, where we are in our time and place. It is very specific to the person.

d) “Demanding or expecting God to continue to uphold a promise that is his means we haven’t understood the redemption that underlies it.”

LB: I may not understand your meaning here. If you’re saying that some of God’s promises are conditional, then, certainly I agree. We do have to be careful not to apply our personal levels of need for rational explanations (or lack thereof) to others. The pursuit that is morally acceptable for one person may not be for another. I make a sinful choice if I “go” where I am not directed to go – even if someone else is directed to go there. I also make a sinful choice if I try to prevent someone from going where God is leading them. It is much more a personal matter than a formulaic one. Some people in my life care very little for rational explanation of matters of faith, others have a very high need for it. At my best (when I am most Christlike), I must honor their individuality for the diversity they represent, and be very careful about labeling anyone’s pursuit as reaching the level of sinfulness.

e) The why of suffering will be worked out “in due course.”

LB: Yes, but just when is that? Monday? March 22, 2018? In practice, if one person is counseling another who is experiencing suffering, or is studying it, it is common for the one with the lower tolerance of (or need for) rational explanations to decide that “due course” comes when they’ve reached their limit. And, as I said above, the threshold is much more individualistic than formulaic.

The Apostle Peter is right (of course!): humility is necessary. And it’s inappropriate for us to stop doing good while we seek all the rational answers we’d like. But I don’t see any “rather than” in Peter’s message. I see just the opposite (particularly in verse 15). So there’s no reason why a devoted follower cannot do both: humbly continuing to do good, and humbly pursuing rational explanations for the hope that is in them, to whatever depth God directs them. According to his advice, we do our best (most Christlike) when, in our own humility, we treat those people (whether they be “insiders” or “outsiders” with gentleness and respect in their own pursuit.

So, for the most part, I agree with what you’ve said, I have intended only to help qualify some things to make them universally applicable. I hope the execution of my intentions was sound, but do let me know if not.

Dear Lynn,

Thank you for your response. I don’t have long. My abcs are not necessarily a match for yours.

a) Yes God does fulfil more objectives than giving himself glory – true. Although if we love God why would we not want to glorify him? I do not subscribe to the view Aristotle had of God- that he is there just for himself. He loves us and cares for us and will do anything to help us for sure. In my experience though he has very good reasons for allowing us to go through things we’d rather not.

b) Rational explanations are generally good for sure. But today we have more education than ever before, and many are doing Phds with comparatively little mission focus. So yes pursuit of ‘rational’ explanations can be wanton and in vain. We can’t assume we are seeking God for his reasons rather than our own.

c) I do agree we need to put a time limit on things sometimes. God understands our exasperation and is not trying to annoy us or keep us in pain, but can use the situation to develop our faith to realise his promise of healing, provision etc.

This is an excellent article, Jayson! Thanks for the well-organized thoughts.

In Christ God shared in our suffering, without interfering. How did he do that? He allowed God to be the Judge of the situation. Surely God is more the Judge of Israel, than he is the patron (in the social sense). Maybe this is why we may tend to interfere more than we intercede as Christians. Our concept is that we are the judge of God through our human cultural and social insights. God doesn’t need us to help him with his PR, but we do need his judgement to purge us of our false judgements of him, and his chosen patronage. Then perhaps he could enlist us in this.

To Nicholas, on the “a-b-c” response…

(For some reason there is no “Reply” button showing after your comment; perhaps the “Comments” system has a limitation on the number in a thread?).

Regarding (your) “a” – “if we love God why would we not want to glorify him?”

LB: Maybe I was misunderstood; I certainly did not intend to give the impression that a Believer would NOT want to glorify God. The intent of my words was to convey that both sides are always addressed: that God is glorified, and the people (and all creation that is impacted) are enriched by his will being done. I did not mean to suggest that one can benefit but not the other. The benefits of God’s will being done always reach both ways.

Regarding (your) “b, part 1” – “…pursuit of ‘rational’ explanations can be wanton and in vain.”

LB: Yes, they can. A stick can be used to kill someone or to make a fire and keep us warm. But we need not go through life fearful of all sticks. I am immensely grateful for Alvin Plantinga, Gregory Boyd, William Lane Craig, John Stackhouse, Peter Kreeft, Alistair McGrath, C.S. Lewis and dozens more who take in a deep draught of our common faith – and can then dive deeply into the complexity of rational explanations and stay there long enough to find treasures God has placed there, and then come to the surface and formulate them so that I and people like me (who are not able to do this on our own) can understand (some) and have our faith and understanding enriched, and then can enrich others. These people are doing God and His Kingdom a great service, and He has equipped them for it. As the scope and depth of knowledge in the world continue, my prayers are that God continues to bring such people along to face what can only be ever more challenges in these areas.

Will there be “wolves in sheep’s clothing”? Sure. But it seems to me that the solution is not to kill everything that looks like a sheep so we can be sure we’ve annihilated all the wolves. It’s to work at the tasks God has entrusted to us. He does call some among His people to be wolf-finders and wolf-neutralizing specialists – and He calls us all to be discerning.

Regarding (your) “b, part 2” – “We can’t assume we are seeking God for his reasons rather than our own.”

LB: No. There should be no assumptions either way: no assumption that a person’s seeking for rational explanations is sinful nor that it is godly. As I said previously, it is a very individualistic thing and we should be very careful about judging someone else’s heart.

Regarding (your) “c” – “I do agree we need to put a time limit on things sometimes.”

LB: Perhaps I was misunderstood, my perspective is the same on this: it is a very individualistic thing and we should be very careful about judging what either the “time” or “depth” limits should be for anyone else.

Thanks for the interaction. I do hope it has been fruitful. If I’ve gone off-track somewhere, do let me know.

Thank you Lynn and to the person who wrote the post. I generally like the people you mention. I haven’t heard of all of them, but know one of them personally. Academics or philosophers and thinkers are wonderful people. I seek to be strict with myself above all (1 Cor. 9 v.27), as I know it is an area where I can over indulge. Also I note that Peter says in his list of qualities to add self-control to knowledge. Personally I believe there are real temptations in the academic world, and yet it’s part of the wonderful world God created, and so as you say, not something to be afraid of.

Nicholas, you are welcome for any positive contribution I could make. May God bless you as you pursue His will (with all your heart, soul, mind and strength) in the work He is entrusting to you.

Thank you Lynn and to the person who wrote the post. I like the people you mention. Although I haven’t heard of all of them, I know one of them personally. Academics or philosophers and thinkers are wonderful people. I seek to be strict with myself above all (1 Cor. 9 v.27), as I know it is an area where I can over indulge. Also I note that Peter says in his list of qualities to add self-control to knowledge. Personally I believe there are real temptations in the academic world, and yet it’s part of the wonderful world God created, and so as you say, not something to be afraid of.