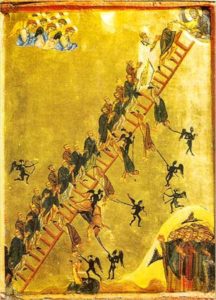

The Ladder of Ascent

The Ladder of Ascent is a spiritual treatise about monastic asceticism. An Egyptian monk named John Climacus (“the Ladder”) wrote this book around 600AD as a spiritual guide for other monks. The book presents 30 “steps” toward spiritual maturity, and focuses on the monastic virtues of humility, renunciation, and purity. More than 500 ancient manuscripts The Ladder exist today, an testament to its popularity on medieval Christianity.

The language of honor and shame runs throughout the 129-page book, available in English here. I will make a few observations here.

The language of honor and shame runs throughout the 129-page book, available in English here. I will make a few observations here.

The goals of the monastic life and ascetic practices were renunciation from the world and communion with God. Renunciation of the world involved foregoing physical pleasures (food, sleep, sex, etc.). However, for St. John, the real snare of the world was social status and honor. Pursuing God meant renouncing any sense of honor or recognition, at all costs. In fact, he admonishes Christians to seek dishonor, derision, insults, and slander as opportunities to learn humility.

Let us pay close attention to ourselves so that we are not deceived into thinking that we are following the straight and narrow way when in actual fact we are keeping to the wide and broad way. The following will show you what the narrow way means: mortification of the stomach, all-night standing, water in moderation, short rations of bread, the purifying draught of dishonor, sneers, derision, insults, the cutting out of one’s own will, patience in annoyances, unmurmuring endurance of scorn, disregard of insults, and the habit, when wronged, of bearing it sturdily; when slandered, of not being indignant; when humiliated, not to be angry; when condemned, to be humble. Blessed are they who follow the way we have just described, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven. (2:8)

While the pursuit of humility is right and encouraging, the author John repeatedly conflates humility with humiliation. The author states that a good abbot should publicly and constantly humiliate monks under his leadership to teach them humility. For example, the author recounts the story of a respected abbot who assigned a new monk to grovel and petition (as a “crazy fool”) at the monastic gate for seven years. This taught the new monk to live without any form of recognition or respect from other humans, thus purifying his soul to hear only the voice of God. This is John 5:44 and 12:43 to the extreme!

In relation to honor and shame, the most extended section is Step 22, titled, “On the many forms of vainglory.” The monk, with great insight, unpacks the corrupting influence of vainglory in our behavior. We humans are addicted to flattery and praise. I was struck how the insights of this person–a monk living in the desert 1,500 years ago—may speak to people today. The passage is cited at length below.

- The sun shines on all alike, and vainglory beams on all activities. For instance, I am vainglorious when I fast, and when I relax the fast in order to be unnoticed I am again vainglorious over my prudence. When well-dressed I am quite overcome by vainglory, and when I put on poor clothes I am vainglorious again. When I talk I am defeated, and when I am silent I am again defeated by it. However I throw this prickly-pear, a spike stands upright.

- A vainglorious person is a believing idolater; he apparently honours God, but he wants to please not God but men.

- Every lover of self-display is vainglorious. The fast of the vainglorious person is without reward and his prayer is futile, because he does both for the praise of men.

- A vainglorious ascetic is cheated both ways: he exhausts his body, and he gets no reward.

- Who will not laugh at the vainglorious worker, standing for psalmody and moved by this passion now to laughter and then to tears for all to see?

- God often hides from our eyes even those perfections that we have obtained. But he who praises us or, rather, misleads us, opens our eyes by his praise, and as soon as our eyes are opened, our treasure vanishes.

- The flatterer is a servant of devils, a guide to pride, a destroyer of contrition, a ruiner of virtues, a misleader. Those who honour you deceive you, says the prophet.1

- People of high spirit bear offence nobly and gladly, but only holy people and saints can pass through praise without harm.

- I have seen people mourning who, on being praised, flared up in anger; and as at a public gathering one passion gave place to another.

- Who among men knows the thoughts of a man, except the spirit of the man within him?2 And so let those who try to praise us to our face be silent and ashamed.

- When you hear that your neighbour or friend has abused you behind your back or even to your face, then show love and praise him.

- It is a great work to shake from the soul the praise of men, but to reject the praise of demons is greater.

- It is not he who depreciates himself who shows humility (for who will not put up with himself?) but he who maintains the same love for the very man who reproaches him.

- I have noticed the demon of vainglory suggesting thoughts to one brother, while he reveals them to another, and he incites the latter to tell the former what is in his heart, and then praises him as a thought reader. And sometimes, unholy creature that he is, he even touches the bodily members and produces palpitations.

- Do not take any notice of him when he suggests that you should accept a bishopric, or abbacy, or doctorate; for it is difficult to drive away a dog from a butcher’s counter.

- Whenever he sees that any have acquired in some slight measure a contemplative attitude, he immediately urges them to leave the desert for the world, saying: ‘Go away in order to save the souls which are perishing.’

- Ethiopians have one kind of face, and statues another; so too the vainglory of those living in a community takes a different form from that of those living in a desert.

- Vainglory incites monks given to levity to anticipate the arrival of lay guests and to go out of the cloister to meet them. It makes them fall at their feet and, though full of pride, it feigns humility. It checks manner and voice, and keeps an eye on the hands of visitors in order to receive something from them. It calls them lords and patrons, graced with godly life. To those sitting at table it suggests abstinence, and it rebukes subordinates mercilessly. It stirs those who are slack at standing in psalmody to make an effort; those who have no voice become good singers and the sleepy wake up. It flatters the conductor, and begs to be given first place in the choir; it calls him father and master as long as the guests are still there.

- Vainglory makes those who are preferred, proud, and those who are slighted, resentful.

- Vainglory is often the cause of dishonour instead of honour, because it brings great shame to its enraged disciples.

- Vainglory makes quick-tempered people meek before men.

- It has great ambition for natural gifts, and through them often hurls its wretched slaves to destruction.

- I have seen a demon injure and chase off his own brother. For just when a brother had lost his temper, secular visitors suddenly arrived; and the wretched fellow resold himself to vain-glory. He could not serve two passions at the same time.

- He who has sold himself to vainglory leads a double life. Outwardly he lives with monks, but in mind and thought he is in the world.

- If we ardently desire to please the Heavenly King, we should be eager to taste the glory that is above. He who has tasted that will despise all earthly glory. For I should be surprised if anyone could despise the latter unless he had tasted the former.

…

- There is a glory that comes from the Lord, for He says: Those who glorify Me, I will glorify. And there is a glory that dogs us through diabolic intrigue, for it is said: Woe, when all men shall speak well of you.6 You may be sure that it is the first kind of glory when you regard it as harmful and avoid it in every possible way, and hide your manner of life wherever you go. But the other you will know when you do something, however trifling, hoping that you will be observed by men.7

- Abominable vainglory suggests that we should pretend to have some virtue that we do not possess, spurring us on by the text: Let your light so shine before men that they may see your good works.8

- The Lord often brings the vainglorious to a state of humility through the dishonour that befalls them.

- The beginning of the conquest of vainglory is the custody of the mouth and love of being dishonoured; the middle stage is a beating back of all known acts of vainglory; and the end (if there is an end to an abyss) consists in trying to behave in the presence of others so that we are humbled without feeling it.

- Do not hide your sins with the idea of removing a cause of stumbling from your neighbour; although perhaps it will not be advisable to use this remedy in every case, but it will depend on the nature of one’s sins.

- When we invite glory, or when it comes to us from others uninvited, or when out of vainglory we decide upon a certain course of action, we should remember our mourning and should think of the holy fear with which we stood before God in solitary prayer; and in this way we shall certainly put shameless vainglory out of countenance—if we are really concerned to attain true prayer. If this is insufficient, then let us briefly recollect our death. And if this is also ineffective, at least let us fear the shame that follows honour. For he who exalts himself will be humbled1 not only there, but certainly here as well.

- When our praisers, or rather our seducers, begin to praise us, let us briefly call to mind the multitude of our sins, and we shall find ourselves unworthy of what is said or done in our honour.

- No doubt there are certain prayers of some vainglorious people that deserve to be heard by God; but the Lord has a habit of anticipating their prayers and petitions so that their conceit should not be increased because their prayers have succeeded.

- Simpler people are not much infected with the poison of vainglory, because vainglory is a loss of simplicity and an insincere way of life.

- It often happens that when a worm becomes fully grown it gets wings and rises up on high. So too when vainglory increases it gives birth to pride, the origin and consummation of all evils.

- He who is without this sickness is near to salvation, but he who is not free from it is far from the glory of the Saints.

This is the twenty-second step. He who is not caught by vain-glory will never fall into that mad pride which is so hateful to God.

There’s a lot of truth here and he does a good job of convicting me of my sin. However, the gospel is conspicuous by its absence. In fact, the philosophy behind all this is closer to Buddhism than biblical Christianity. (You eliminate desire to reach enlightenment, but if you WANT enlightenment, you are tangled by desire.) So, unfortunately, from a biblical evangelical perspective, the broad thrust of these admonitions is more likely to drive me to despair. You MUST have the gospel!

Agreed, Ant!

Ant, good points. What you describe is a defining feature of Christian monasticism, which was the predominant expression of Christianity for ~1,000 years. The idea of asceticism is that certain physical practices (i.e., fasting, renunciation) can aid our battle against Satan and help us overcome sin. In their mindset, such self-negating actions re-enact the shame and suffering of the cross in order to obtain the power of the cross. Though not mentioned here, contemplation of the cross was common monastic practice as well. I’m just explaining (not defending) the mindset of ancient monastics, which obviously differs from our contemporary approaches to spirituality and sanctification.

I shared about The Ladder of Ascent, not because it articulates the biblical evangelical position, but it offers a window into Christians in other ages and contexts struggled against vainglory/false honor/pride. I often find these interesting, both theologically and historically. I have to admit though, when reading ancient Christians, I oscillate between “this guys are crazy!” and “that’s a great insight!”

I have always found elements of monastic living & mindset to leak the aroma of a “works based salvation.”

Thank you Jesus for your gift of grace on the cross.